In May 2004, I rewarded myself for my first sub-40 10k: I bought a Garmin GPS watch. They were big and clunky and expensive. My biggest regret was not spending the extra $100 for the heart rate option. Sometime in 2006 I corrected that oversight and have been running with a heart rate monitor ever since. Almost every training run and race since that time has been logged with heart rate data.

So with six years experience training by heart rate, I was very interested to read about iRun’s “8 Important Rules for Heart Rate Monitoring” (see note 1). There are some things that beg further discussion, based on my own experience. And remember I am more of an average runner training with a HR monitor, as opposed to top coaches training Olympic medalists.

Any numbers I mention are based on someone around my age (47).

1. Heart Rate Zones Developed by Predictive Equations are Not Accurate

Agree. However, predictive equations, such as Max HR = 220 – age, remain a good starting point until you personally get to know what your own Max HR really is. If you understand the term “throwing yourself onto your sword” you will know the sacrifice that is required to reach or exceed your Max HR. This typically won’t come until the final sprint at the end of a 5k race, and usually you are thinking about throwing up.

Another point is that seasoned and exceptionally fit older runners may exceed their age predicted Max HR by 10 bpm or more. They really have the heart of a 30 year old! By the way, that is definitely not me – after 172 bpm hand me a bucket, cause I going to hurl. The predictive equation fits me very well.

If you are new to performance based training, the final point is why risk a major cardiac incident? Get your doctor’s okay and an ECG before putting your heart under this kind of duress. Best to keep your HR under 80% of your predicted Max HR until you have the green light.

2. Heart Rates are specific to the Activity

Agree, almost. Not explained is that circulation, especially venous return, is aided by body movement. The more your body moves, the less your heart has to beat for a specific energy output. For example, for about the same HR of 150, I can burn 750 cal/hr sitting on the bike (legs only), 900 cal/hr on the treadmill (legs and a bit of arms), and 1050 cal/hr rowing (legs, core and arms).

However, Max HR does not change with the type of activity. Once you have hit your limit that is all you can do.

3. During Steady State Training, Pace Should Remain Constant as Heart Rate Increases

Holding a constant pace on a long run (especially a marathon) will have this effect. However let’s be clear, this is not “steady state” rather quasi-steady state. In conditions of steady state, all factors including heart rate must be in equilibrium. As we run longer distances, our muscles begin to tire and our energy consumption (sugar vs. fat) changes. Our efficiency begins to decrease and in order to maintain the same net output (same pace) we have to work harder, leading to increase in heart rate.

A rising heart rate is an indication you are running out of gas, and hopefully the finish line is near. Drain the tank, but leave just enough to get across the line. This is part of the gamble of marathons. Knowing your average goal HR (mine is 151 bpm) for a marathon certainly helps; most of your marathon should be run near this rate. I managed to finish this year’s Boston by keeping my HR in check until 23 miles; by the time I hit the finish I was at my max (172 bpm).

4. When Training in Hot Weather or Periods of High Stress, Use Feelings of Fatigue and Comfort Rather than Heart Rate

Don’t believe it! You should use all of them. An easy run should always be an easy run, by feel and by HR. The best way to ensure you having an easy run is to monitor your heart rate, which should be around 75% of max. Heat is an added stress, and you should expect a higher HR when first to exposed to hot conditions. So adjust your pace to suit on warmer easy runs. Eventually you will acclimate; your HR and pace will return close to normal.

However, for hard training days, a touch of hot is an excellent way to make a session harder without stressing muscles and tendons. So doing a tempo at your usual pace in warm weather, at up to 160 bpm instead of the usual 150 bpm (for a fit 47 year old), can work wonders. Imagine how easy our fall races will be! How about hot Yoga training for the Boston Marathon? It apparently worked wonders for some participants.

So you need to ask yourself what is the purpose of my run today. If it is to achieve a particular hard work response, then your HR will have to be higher if it is warmer to get the same effect. If it is to have a good recovery, then stick to target easy HR regardless of the weather.

Caution: If training in extremely hot or humid conditions, an elevated (near max) HR is a sign of heat exhaustion. Time to find a cool place fast!

5. Don’t Compare Your Heart Rate to Others

Why not? Open a discussion. We can learn things from each other.

A better idea is that we each need to know our own limits and performance points. My easy run could be nearly race pace for someone else. Yes, you too can train with a Kenyan on their easy days (not that I am one).

6. Using Heart Rate to Gauge Interval Training is Not Accurate

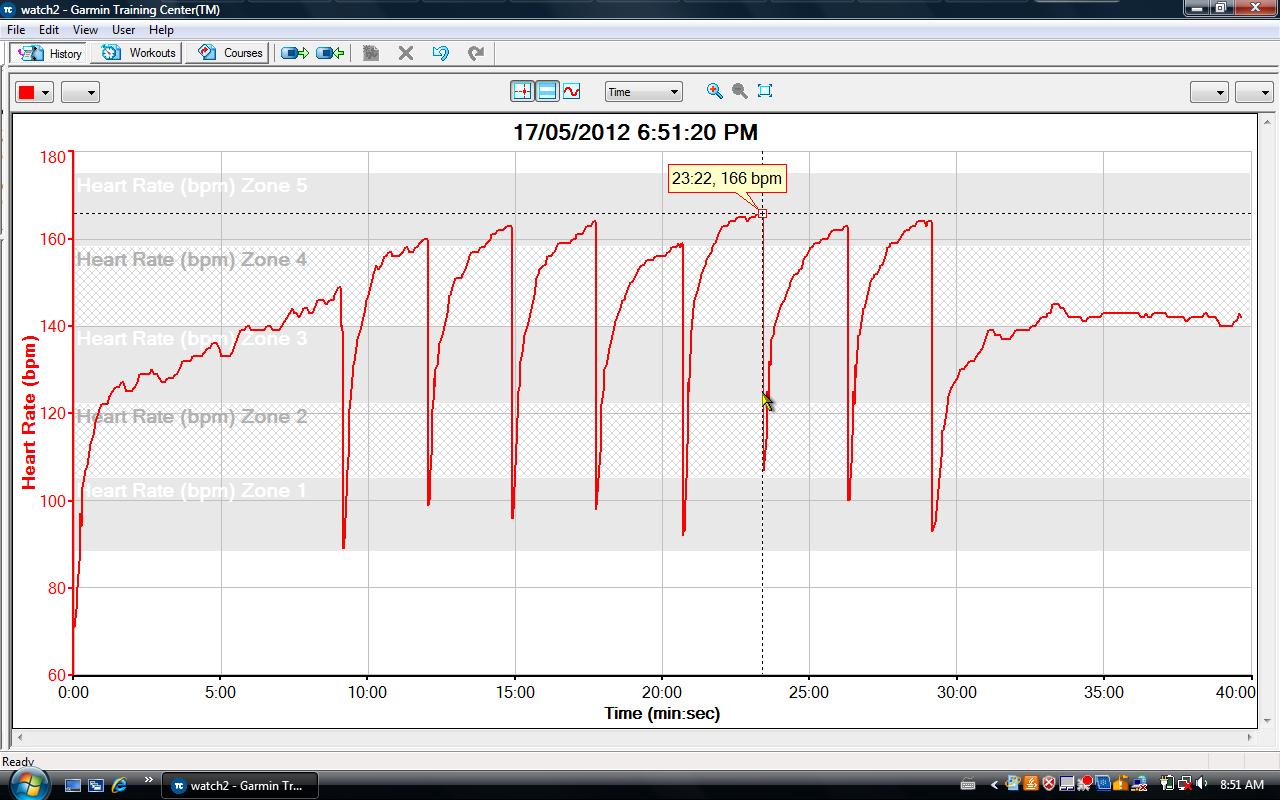

Agree, almost. The main reason is that HR starts off low and quickly ramps up; this is not a “steady state” activity. The maximal hr (not necessarily your Max HR) occurs just as you finish each interval. Take note of this value. How close were you to your max? As you progress through each interval, assuming same pace, you will find that your maximal HR increases. This is a lot like item 3.

Download your data and look at your HR curves for each repeat (see below for example). You will notice that HR tends to plateau somewhere shy of your max HR. Expect this for shorter intervals (400/800) as your heart rate tends to lag; longer intervals will take you closer to your Max HR (1200/1600). The faster you hit your plateau and the longer you can hold onto it during your interval is a good indication of the effort expended, and level of fatigue experienced.

Intervals also permit you to relate discomfort to your faster heart rates. Let’s face it, we race more by feel than by staring at our HR monitor. If we can replicate that necessary level of sacrifice during training, then we can zone in better on race day.

7 x 800 m intervals with warm up and cool down, average 2:50 per 800 m.

(recovery periods between intervals not shown).

7. Heart Rate Should not be used to gauge recovery between intervals

Of course it should! After you wait the requisite time, wait a bit longer if your HR has not dropped below 70% to 75% of your max HR. This will likely be the case during your last few intervals.

Also, the time it takes for your HR to settle below 75% after a hard interval is a great indicator of cardio and overall fitness. The shorter the heart rate recovery time the better. Just remember to always give sufficient time for complete lactate clearance.

8. Unless you are testing, you are guessing.

Hmmm. Save the VO2 test until you have spent some time training with your HR monitor. Until then, the general rules of “easy” being less than 75% of max HR, and cardio-intensive exercise being at least 65% of max HR came from exhaustive clinical studies.

But with any kind of study, there are typically variances. The real point goes back to item 1: each of us is different. Use your HR monitor and get to know your performance points. Without a heart rate monitor, you truly are guessing.

That written, if I found $200 under my seat I would get a VO2 max test tomorrow. See www.myvo2.com for testing in the Pickering/Ajax area (conveniently located at Running Free Ajax).

Note 1: Some differences between online version and printed version which this article references.